Impressions of the James Castle Shed and Trailer

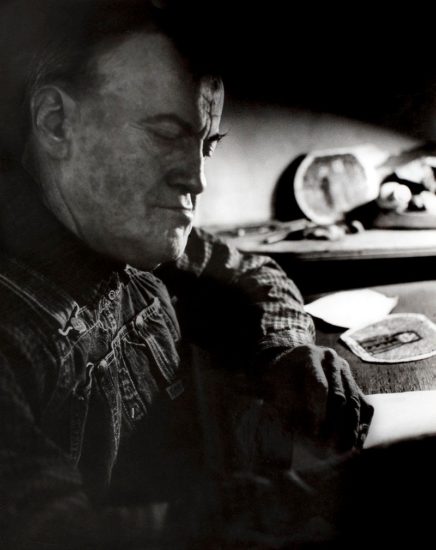

Born in 1899 in Garden Valley, Idaho, artist James Castle gained worldwide renown, with his works in the collections of institutions such as the Smithsonian Institute and the Whitney Museum. A major figure in American folk art, he was also deaf, communicating primarily through his art, which relied on humble materials such as soot, spit, cardboard, and string. Self-taught and highly prolific, he spent his entire life in Idaho.

A photo of James Castle.

From 1931 to his death in 1977, he lived and worked in Boise, first in his family’s house, then in an old shed on the property, and finally in a secondhand trailer purchased in 1963 with income from the sale of his drawings. When the city of Boise acquired the Castle property in 2015, the family house was renovated to house an artist-in-residency program. The next step is to preserve the shed and trailer—no small feat, given that the structures have been battered by many decades of Idaho’s long, snowy winters. The city asked ARG Conservation Services to devise conservation recommendations for this unusual project.

When I visited Boise and first saw the shed and trailer, they reminded me of how simple our lives can be if circumstances require it. These homes of Castle’s were very, very small. Yet Castle lived and worked in them and became an internationally known artist.

Castle’s work is known as “outsider” art. At first, it appears to have a simplicity that makes it easily accessible. Upon further study, it becomes clear that there is an emotional depth to his work that is the hallmark of all important artwork.

There are similarities to our David Ireland House project, which involved conservation of the conceptual artist’s home in San Francisco, a dilapidated 1880s Victorian that Ireland began transforming into a work of art in the 1970s. Both artists used their artistic media in fairly simple, unrefined, and direct ways. Both projects are about the preservation of residences, and both required stabilizing everyday materials rather than formally executed artwork.

The shed where James Castle lived and worked beginning in the early 1930s.

But there are some differences. Castle was not a trained artist, as Ireland was. It appears that Castle lacked the self-consciousness that is more characteristic of a trained artist. Also, Castle’s two homes have an overall ephemeral quality to them, while Ireland’s house is much more durable (except for the mud patties and the sticky notes Ireland added to the interior). The preservation of Castle’s homes is more about stabilizing two precious objects rather than preserving a building, as with Ireland’s house.

Examples of James Castle’s artwork.

The Castle and Ireland houses are both fairly unusual in that they are artist-residences-turned-galleries. I don’t believe I’ve worked on any other projects in that category, except perhaps the Frank Lloyd Wright Hanna House at Stanford University. There, every component of the building is considered historic, and we developed treatments appropriate to the highest level of conservation. But Wright was the designer, and others executed his design. With Castle and Ireland’s residences, the hand of the artist was everywhere.

In storage: the trailer that was Castle’s home and studio from 1963 until has passing in 1977.

The conservation recommendations we make for artist residences like these, so closely woven into the artist’s work, are different from those we would make for other kinds of buildings. With both the Castle and the Ireland projects, we treated and conserved every part and finish of the structures as artwork. Typically, conservation of buildings involves introducing new materials to extend the life of the existing fabric. For Castle and Ireland, enabling reversibility of conservation treatments is very important. In the preservation of more conventional historic buildings, reversibility is generally less feasible, though still a goal.

Left: inside Castle’s shed, 2018. Right: the shed next to the renovated main house.

Castle’s homes, in particular, have made me aware of the impact of an artist’s surroundings on their work. They impressed on me that an artist’s residence tells a story about them and their artwork. Seeing how an artist lives and crafts their surroundings provides a new window into understanding their work. It was poignant to see the very modest homes of this deaf artist and know that, although he rarely left his neighborhood, he felt compelled to pursue his artwork with fervor his entire life.

Photos graciously provided by James Castle House and The City of Boise Department of Arts & History.